MY FATHER, ROBERT LOUIS REUSCHE

I do not know very much about the life of my father. What little I know can only be pieced together by the scraps of information that I heard over the years. It’s not that I forgot a lot. He was in and out of my life, and there were few family connections.

My grandfather is Leo Louis Reusche born 13 November 1891 in Lyons, Iowa and baptized 8 December 1899. Leo Louis has a sister, Belle Winifred Reusche born 17 June 1894 at Lyons, Iowa and baptised 8 December 1899.

My paternal grandfather Leo died …. I don’t remember ever meeting him. I only have some faint memory of him based on a conversation I had with his second wife, Rhea. I met her a few years before she died in in 1981 and asked her a lot of questions about Leo. I recorded the conversation. But I have no idea what happened to the recording. Life is much easier these days for saving and accessing information.

My paternal grandmother is Grace Eleanor Reusche King. She was born July 25, 1897 in Missouri and died February 17, 1988 in Los Angeles. Leo and Grace had two children. My father’s older brother is John Leo Reusche born 7 May 1915 and baptized 14 July 1917. I met him on a number of occasions. He was married a number of times. My mother called him a “ladies man.” (I wonder how she would describe her two oldest sons?) I met Grace once in a nursing home towards the end of her life. Sandy tried to stay in touch with her.

I met Grace once. For whatever reason, I was always discouraged from meeting her. At the end of her life, when she was in a nursing home, I managed to convince my father, with Hanny’s help, to visit her. As I recall, Sandy kept up visits at this time but even though she lived reasonably close, I don’t think they met too often either.

My grandfather was married twice. His second wife is Rhea Armena Reusche, born 1 December 1893 and died Nov 1981 in Los Angles, Van Nuys, California. Rhea was a part of our family, unlike Grace Eleanor.

My great grandfather was Julius Reusche and my great grandmother was Janet Reusche. Records from Clinton, Iowa indicate that Julius died of pneumonia when he was 36 years old on 17 July 1898 (born 1862?). He apparently was a blacksmith. Rhea said that he was killed by a horse, but the records say he died of pneumonia.

Thanks to the efforts of Ray Reusche and his wife, I have the following genealogical information.

My Great-Great Grandfather was CHARLES REUSCHE, baptized at St. Michaels Church, in Kranichfeld, Thuringia, Germany as JOHANN HEINRICH KARL THEODOR REUSCHE and was born 29 August 1831 in Kranichfeld Thuringia, Germany. He was “Americanized” when he emigrated to the US in the 1850’s. He settled for a very short time in Illinois (not Chicago) before moving to Lyons, Iowa, where he and his wife put down their roots. Charles Reusche married Julia Becker and had 6 children, one of whom was Julius Reusche, my Great-Grandfather (2 other children were Adolph and Charles).

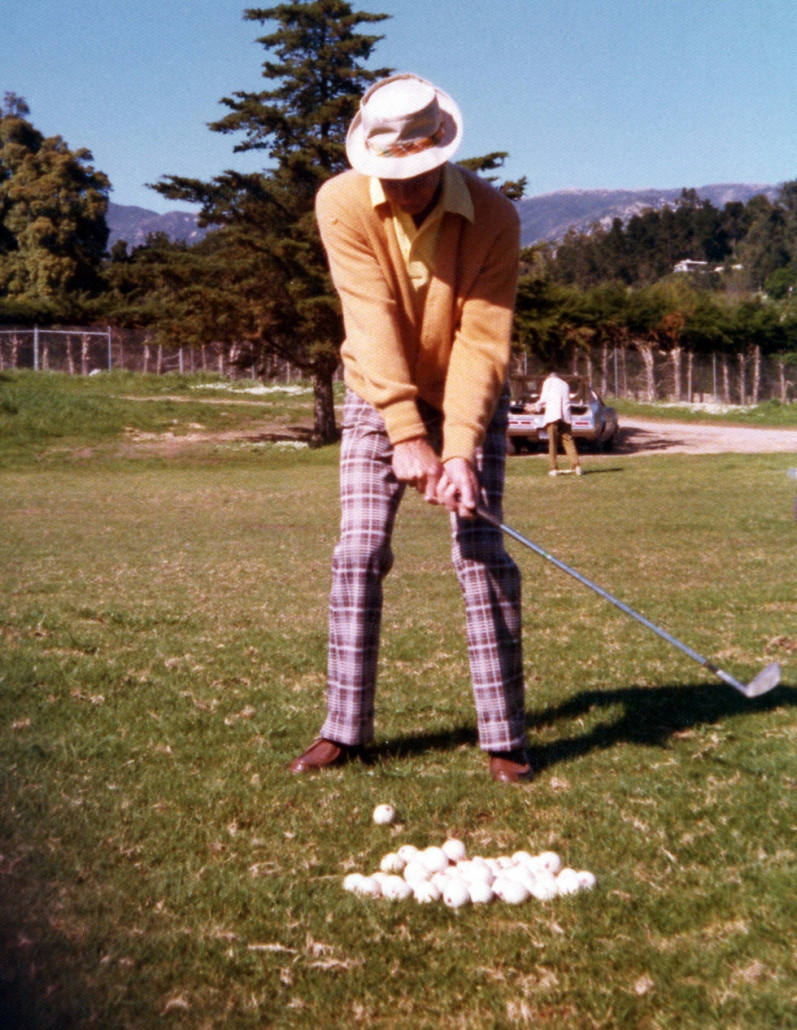

What I know about my father’s home life is that he was unhappy and seriously impacted by the divorce of his parents. The issues apparently destroyed family intimacy. My father after his divorce did not stay in touch with us. He said it was because of his negative experiences as a child. But he was always available if we reached out to him. He did not discipline me or the others. If we listened, he would gently give us his opinion. He loved sports, and played semi-professional basketball. All his life he was an active sportsman, basketball, tennis, golf, badminton and probably others. He gambled a bit especially playing golf and card games at the clubhouse, but small stuff, and according to him he always made some pocket money.

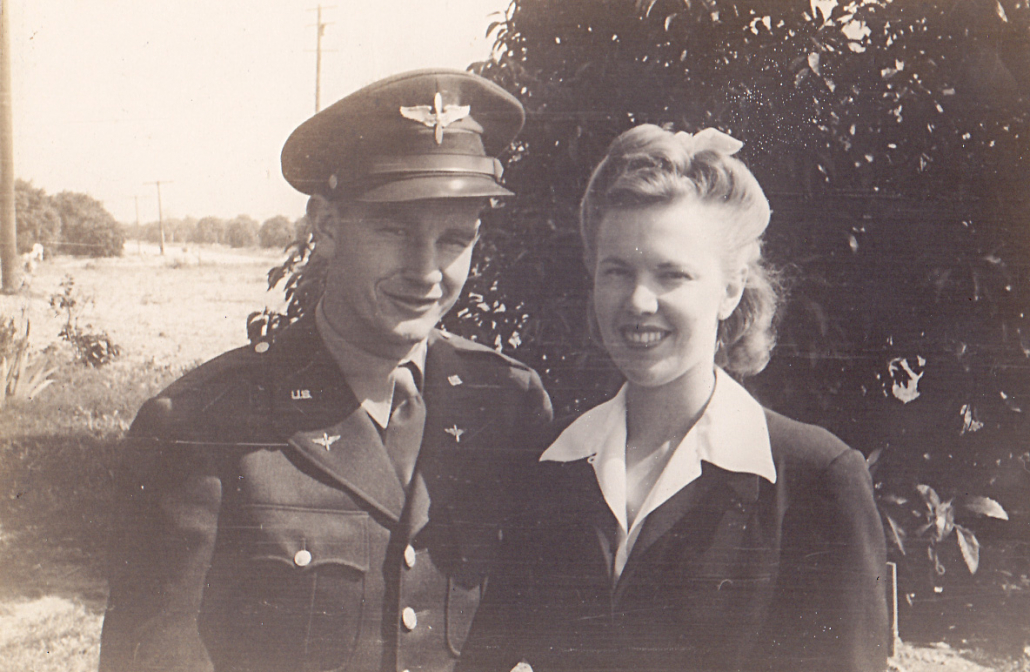

Professionally he was successful. But he never showed it to the children, at least I never saw it. He was an air force pilot, worked until early retirement at 50, and never worked again. A Lt. Colonel, officer; his rank was not a gift. It had to be earned.

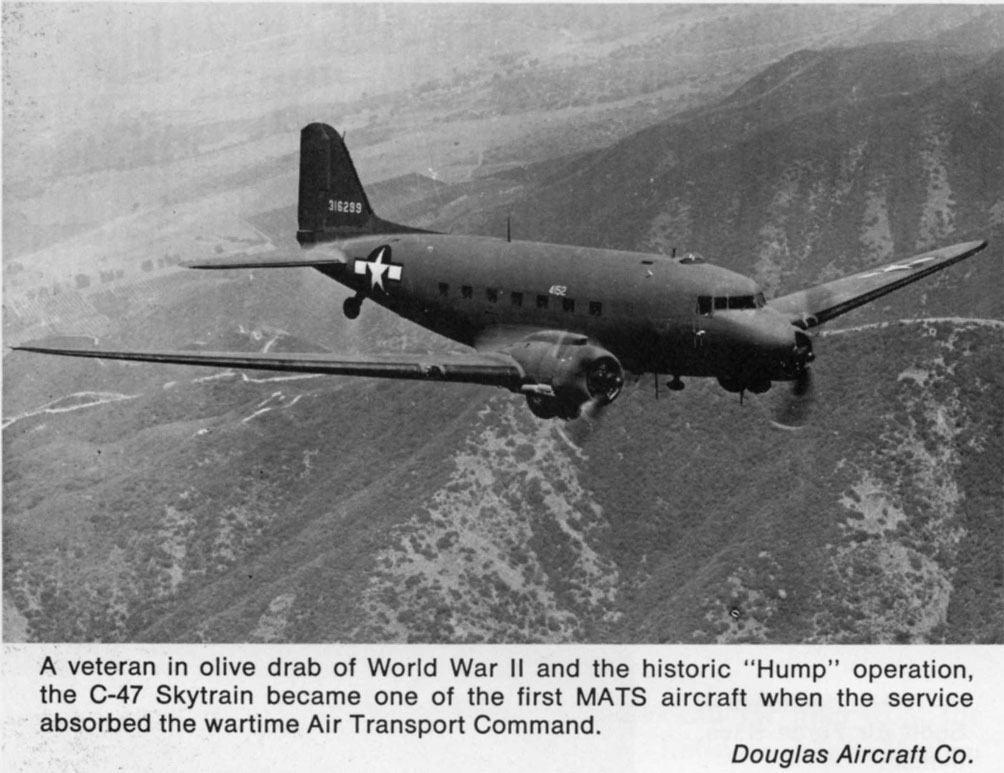

I talked with my brother and asked what he knew. My father started flight training in May 1942 and received his “wings” about a year later. He was 25 years old and it was World War II. After pilot training he was trained in the C-47 transport and was assigned to the Pacific theatre (India, Burma, Southeast Asia). I can remember encouraging him to talk one time and he mention his time “flying the hump” in the Burma theatre.

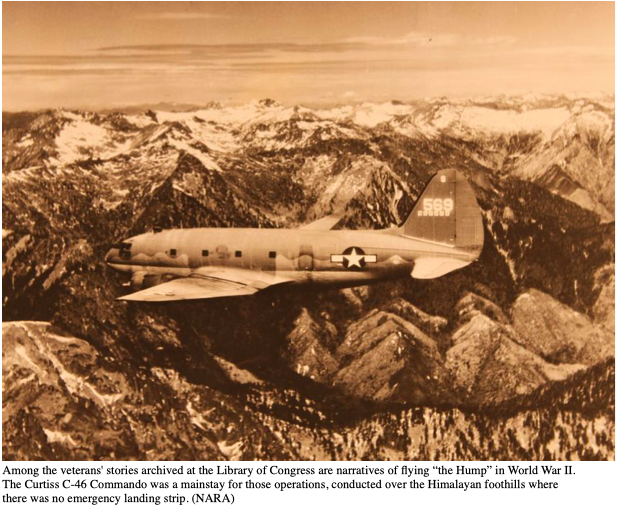

The Hump was the name given by Allied pilots in the Second World War to the eastern end of the Himalayan Mountains over which they flew military transport aircraft from India to China to resupply the Chinese war effort of Chiang Kai-shek and the units of the United States Army Air Forces based in China. Flying over the Himalayas was extremely dangerous and made more difficult by a lack of reliable charts, an absence of radio navigation aids, and a dearth of information about the weather. The Air Transport Command’s India-China Wing (December 1942-June 1944) and India-China Division (July 1944-November 1945) was the responsible military organization.

The airlift began in April 1942, after the Japanese blocked the Burma Road, and continued daily to August 1945, when the effort began to scale down. The India-China airlift delivered approximately 650,000 tons of materiel to China at great cost in men and aircraft during its 42-month history. For its efforts and sacrifices, the India-China Wing of the ATC was awarded the Presidential Unit Citation on 29 January 1944 at the personal direction of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, the first such award made to a non-combat organization.

Living conditions in the humid, jungle-like atmosphere of the Assam Valley were very primitive. Personnel lived in tents and bamboo bashas. Food was military C-rations as no eating off base was permitted for health reasons. Dysentery and malaria were always health threats. All drinking water had to be purified before use. Personnel had to sleep in mosquito net covered beds. Entertainment was very limited.

Apparently Bob also did not know much about the details of my father’s life. They both were career military pilots.

Crossing the Hump – World War II activities of my father

(Below is an article, one of many stories in the Library of Congress archive of war reminiscences. My father was one of the pilots.)

The Library of Congress Veterans History Project collects the first-hand remembrances of U.S. military veterans so their stories will be accessible to future generations.

A search for “China-Burma-India” in the World War II section turned up the account below. We were hoping to find experiences of pilots who had flown the treacherous supply route from India to China by which the United States and Great Britain supported China’s fight against Japan. The transports would take off from airfields in India loaded with food, weapons, and fuel, and fly across the foothills of the Himalayas. Crossing “the Hump,” as the pilots called the route, was some of the most dangerous flying of the war. The pilots saw few Japanese fighters; instead, they battled mountain weather and rudimentary navigation aids. So many crashes marked the 550 miles of the Hump that by the end of the war, crews were calling it “the aluminum trail.”

Most of the airplanes crossing the Hump were Curtiss C-46 Commandos or the ubiquitous Douglas C-47. The flights were very dangerous—and they took the lives of so many.

Over the Hump

The following account from First Lieutenant Milton Richard Buls — C-87 pilot, part of the Air Transport Command’s mission in the China-Burma-India campaign. (My father was also with the Air Transport Command, but he was a Major and was the senior pilot).

“It was the monsoon season. Usually they would taper off just before we got to Luliang, which was the first radio beacon in China where we made about a 45-degree turn to go to Kunming where we delivered our fuel. Every route from India ended at Kunming. From there we would sometimes go up to Chengdu and Loeping. We had very little by way of navigation aides, but two low-frequency, low-powered beacons.

Near the end of the monsoon, we started getting very high tailwinds. Normally it was about a three-hour flight to Luliang. We flew for three hours, and couldn’t get anything on the radio but static. So we flew another hour, not knowing what our ground speed was. All of a sudden we broke out of the clouds and bright moonlight reflected on the water. We had gone all the way across China.

In the distance we could see a big island—Formosa [now Taiwan]—which was still Japanese-held territory. We made a quick turnaround and got back into the clouds. After a total of 13 hours and 10 minutes in the air, we finally got to Kunming. We were so close to running out of fuel that the number four engine quit as we were letting down, and when we got on final approach, number one quit.

We were not able to deliver any fuel at all to them; in fact, we had to take on enough fuel for a six-hour flight back to our base in India. We calculated that we had about 90-mile-an-hour headwinds.

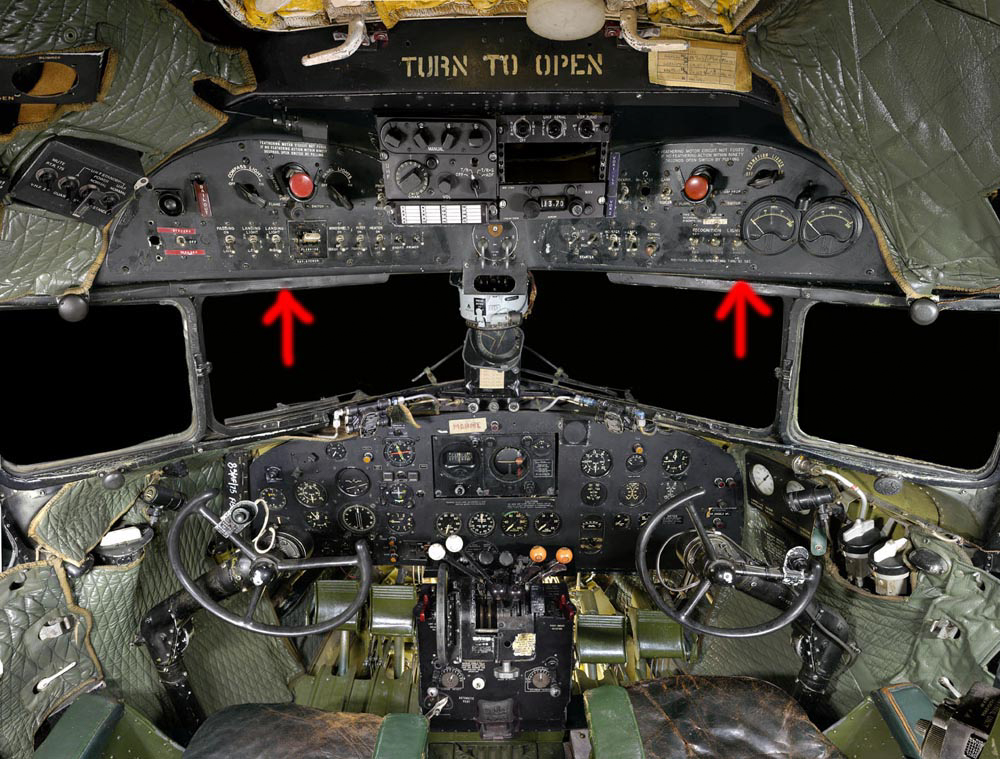

We had very few instruments: primarily needle, ball, and airspeed. We had an air-driven gyroscopic compass and an artificial horizon. I think we had about 30 degrees of bank, and 45 degrees of pitch, and if you exceeded that, the instrument would tumble and become worthless. Once in a while, you would get into a thunderstorm that would spill all your gyro instruments. Then you had nothing but the needle, which gave you left and right, and the ball, which told you whether you were slipping or skidding. The airspeed was the only indication you had if you were going up or down.

If the airspeed increased, you knew you were going down, so you would pull back on the stick. At that point you were straight and level. This was really hard to do in the extreme turbulence of a thunderstorm. On one occasion, we actually felt as though we were in a dive on our back, and all we had was the airspeed indicator, which was really winding up. We knew we were in a dive; we didn’t know which way was up, but we managed to straighten out the wings with the ailerons and rudder, and then pull out, pull back on the stick until the airspeed started dropping off.

When we hit about the bottom of that loop, we broke out from underneath the clouds. It was night, and we saw what looked like four lights in a row. They were actually smudge pots, cans with rags and kerosene in them to give you light, to show the edge of the runway. We knew we were almost at Myitkina, which was an old fighter base. It had been in Japanese hands just a few days before. But we were so badly banged up we couldn’t have gone anywhere else.

The airplane was twisted completely out of shape and was almost uncontrollable. Anyway, we proceeded on to those lights and sure enough it turned out to be [Myitkina]. We landed and shut down the engines. There were a couple of Americans there who had just come out of the jungle. They said that a few days before, they had cleaned the Japanese out of there and wanted a ride home. But the airplane was unflyable; we had popped many rivets, and the horizontal stabilizer was twisted about 10 degrees off of horizontal.

Standing behind [the aircraft], you could see that [it] had been twisted badly. In the course of that dive we hit hail, and with the speed we reached in that dive, we lost the cowlings off all four engines. The next morning we contacted our base in India, and they sent a C-47 from the rescue squadron, which picked us up and took us back to our base.”

Berlin Air Lift

After his activities in the Pacific region, he moved to Europe and flew in the Berlin Air Lift. The Berlin Blockade (24 June 1948 – 12 May 1949) was one of the first major international crises of the Cold War. During the multinational occupation of post–World War II Germany, the Soviet Union blocked the Western Allies’ railway, road, and canal access to the sectors of Berlin under Western control. The Soviets offered to drop the blockade if the Western Allies withdrew the newly introduced Deutsche mark from West Berlin. In response, the Western Allies organized the Berlin airlift to carry supplies to the people of West Berlin. The Berlin Blockade served to highlight the competing ideological and economic visions for postwar Europe.

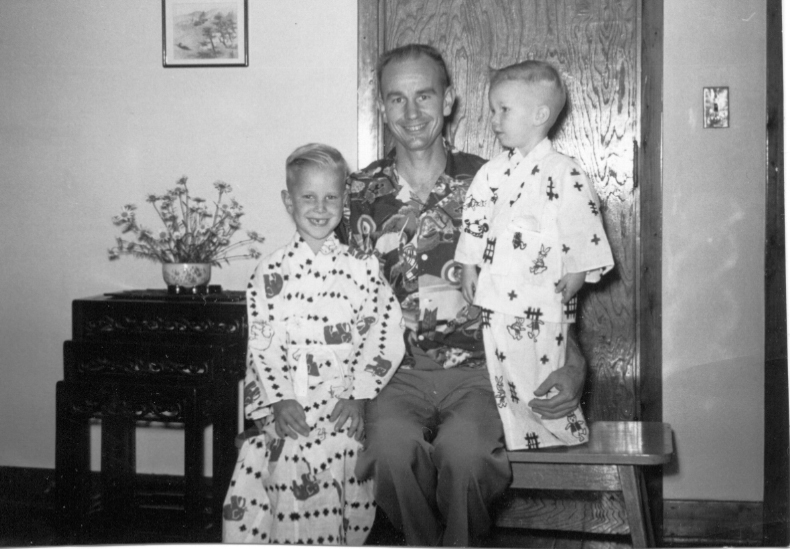

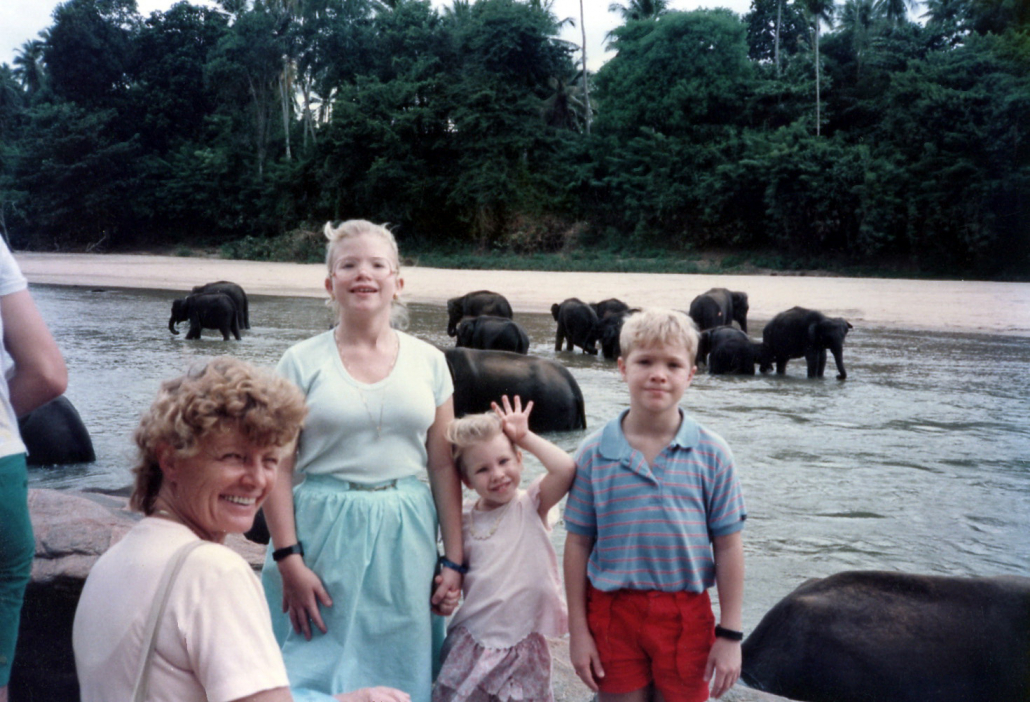

By early 1951 my father was back in California because that is when I was conceived. Soon thereafter, he was in the Korean war (1950-1953). He moved to Japan with my mother and 3 children: Sandy, Bob and me. In Japan we lived in the Grant Heights Housing Area (Air Force). The following is from another family, but it is essentially the same as my family’s story: “In 1955, my family sailed from San Francisco to Tokyo on a WWII military transport. The voyage took two weeks and everybody …got seasick, My father never told us what he did there although we always suspected it had something to do with electronic eavesdropping on the Soviets. The U.S. military had bases all over Japan during years after the occupation and by the time we came the presence of so many military families in the Tokyo area had resulted in the construction of several family housing areas such as “Grant Heights” in northwest Tokyo. Hundreds of American service member families lived there – thousands of kids. I remember it much like a small town in America with its own elementary, middle and high school, a commissary, base exchange, movie theater, swimming pool, gymnasium and four little league baseball diamonds where I played ball every summer.”

After Japan he was transferred to Scott AFB in Honolulu, Hawaii (1954-57). This was before Hawaii was a state; it was an US protectorate until 1959. Our house was located at 510 Julian Avenue, Honolulu. Bobby remembers that, from our house, you looked directly out to the channel and it was most interesting when the ships were coming in and going out. The Officer’s Club pool was down the street to the left next to the club (no longer there). The pool was elevated and a good place to watch the ships move. As a kid it was most impressive to see the carriers go by with all the planes and the sailors lining the flight deck. Bob wrote: “On my cruises I was able to line the deck and look at the pool.”

After Hawaii, he was transferred to the Pentagon (1958-1963) and, as he put it, he was flying a desk. I assume he had some kind of military intelligence role until the end of his career, because he had a couple of stints overseas working out of Embassies.

My father’s retirement record shows that he received the Distinguished Flying Cross with 1 Oak Leaf Cluster (signifies a subsequent award), Air Medal with 3 Oak Leaf Clusters, Meritorious Service Medal, and others.

– Hawaii

– McLean

– Laos

– O’Fallon

– Turkey

– Florida

27 June 1961 – transferred to Laos for about 1 year. I was 9 years old living in McLean, Virginia. I was probably in the 3rd grade. Sometime before this event, I remember fights between my mother and father, ending up with my mother throwing my father’s things out the front door— maybe that explains the assignment in Laos. I also remember my mother bringing me for the “reconciliation,” a meeting at an Officer’s Club. I suspect this was somewhat before he left for Laos. When he returned from Laos in July 1962 we moved to O’Fallon, Illinois.

I have memories of my father between 1962-1965. He lived in the family home for part of this time, and I witnessed fights between my parents. Sandy tried to protect her younger siblings (Scott and me) from these events, but of course we saw them. I think the culmination happened one evening which I remember distinctly. I remember my father sitting in his habitual chair, reading and doing the crossword puzzles. Not talking much but available if you approached him. On the “final evening” my mother picked a fight with him. The fight grew loud and they moved to another room (so the children would not be witnesses). My mother slapped my father a number of times; finally my father slapped her back. My mother of course chided him for hitting a woman, and he was gone. The next memory is a story about my mother trying to run over my father with a car. Finally, I remember meeting my father at the swimming pool, when he was living in the officer’s quarters at Scott Air Force Base.

During this period I often went to the golf course with my father. I caddied for him, and also learned to play with his help.

After the divorce from my mother, my father was transferred to Turkey. From 19 October 1965 to 9 November 1967 he served as an agricultural attache in Turkey. He never talked about this work either, perhaps because it was classified as “secret” by the Military, but I think I heard somewhere that he was involved in electronic eavesdropping on the Soviet Union during the cold war.

When my father went to Turkey from O’Fallon, Illinois, my mother with 3 children moved back to McLean, Virginia during the summer of 1965. My bother Bob entered the US Naval Academy in the summer of 1965. My mother pushed all her sons (me included) to enter one of the military academies, and was successful in 2 out of 3. I grew up in the 60s and was definitely part of the counter-culture crowd— and being in the military was not an option. My bother visited dad in Ankara in the summer of 1966 during his 6-week summer vacation from USNA, flying out there on military transports space available.

Between the summer of 1965 and November 1970 I only saw my father once. This was probably at the end of 1967 or 1968 after he returned from Turkey, because Beverly was with me when we met. The next time I saw him is when I went to Tampa to visit him with Hanny, probably during spring break in 1970, and again in November 1970 on my easy rider motorcycle trip.

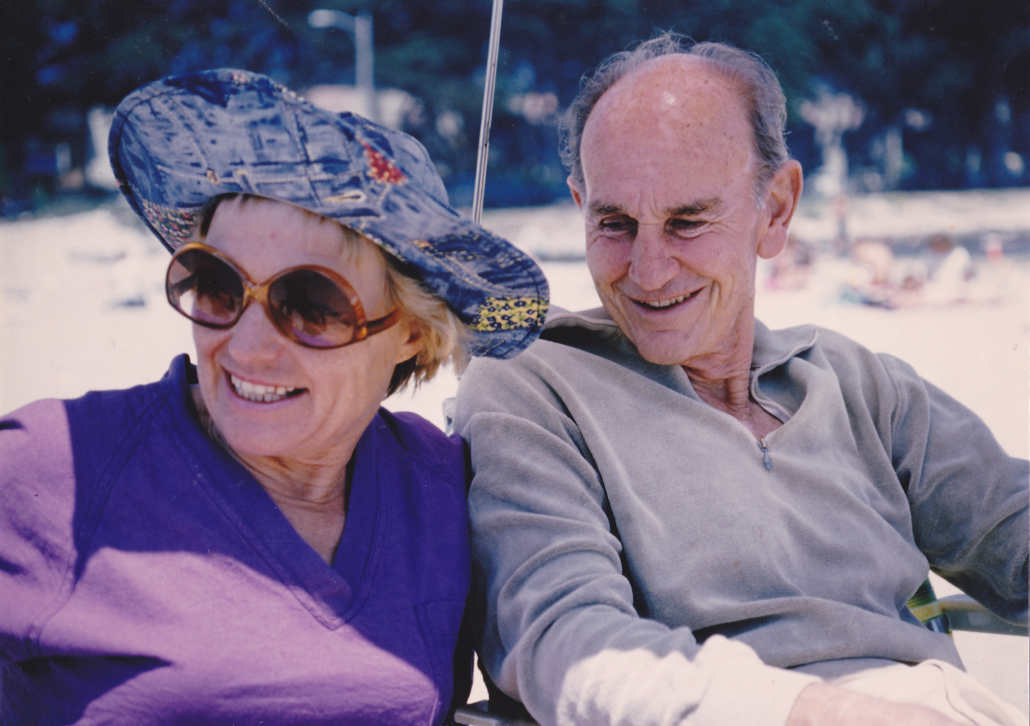

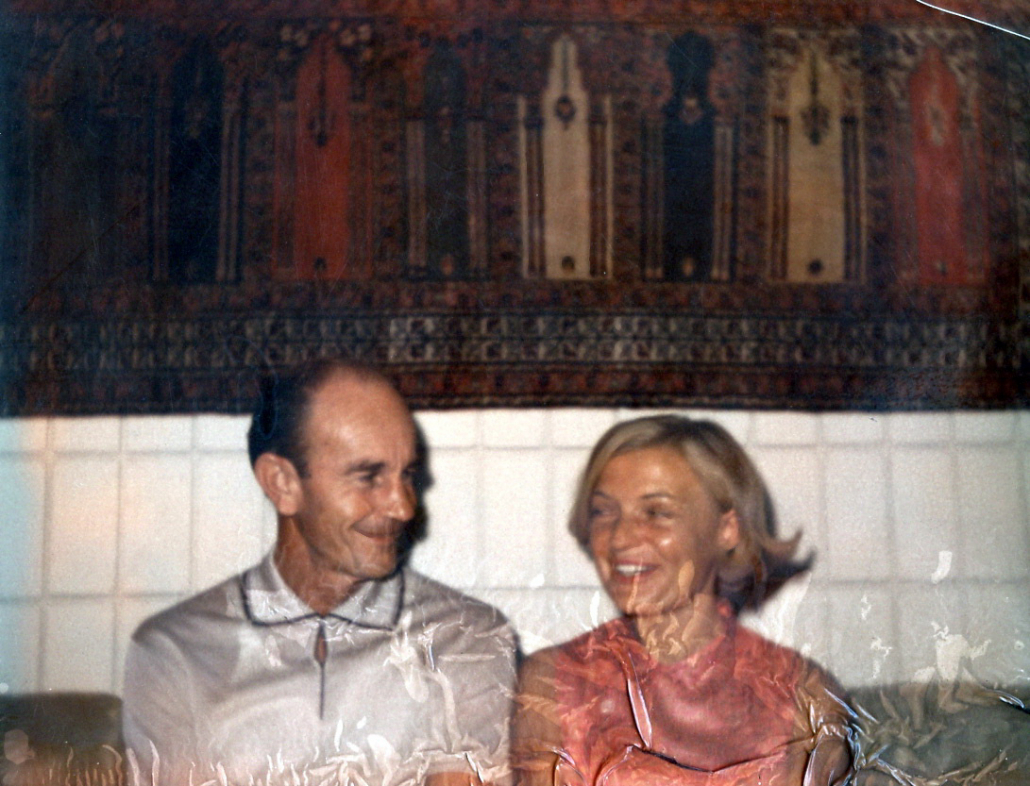

My father’s second wife was Hanny Visser Reusche. Hanny is Dutch, and her Netherlands address was once given as Burgem Verwielstrat 41, Oisterwyk, (N. Br.), Holland. A VISSER P.M. still lives at this address. She was born 16 June 1935. She met my father in an airplane to Ankara Turkey where she was traveling to work in the Netherlands Embassy and my father was starting to work as a military attachee at the US Embassy. They often told the story of how they met in the airplane. My father offered to light her cigarette, which Hanny did not really appreciate. Then, the next morning, at their hotel, they meet again. As I recall the story, they practically bumped into each other in the hall of the hotel. Their hotel rooms were close together.

Apparently my father and Hanny started their journey with one common trait. Hanny did not like talking about her life in the Netherlands. She was a child during the 2nd year war, and was traumatized by the bombings and German occupation of the Netherlands. After her school, she said she travelled around Europe, at times hitching rides. Typically Dutch.

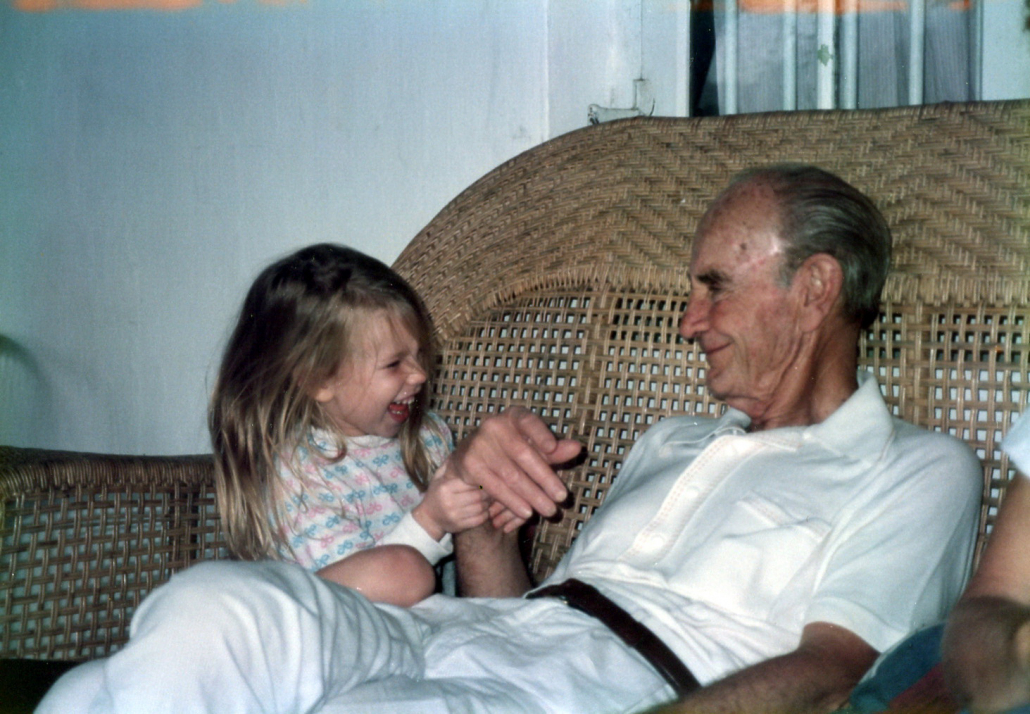

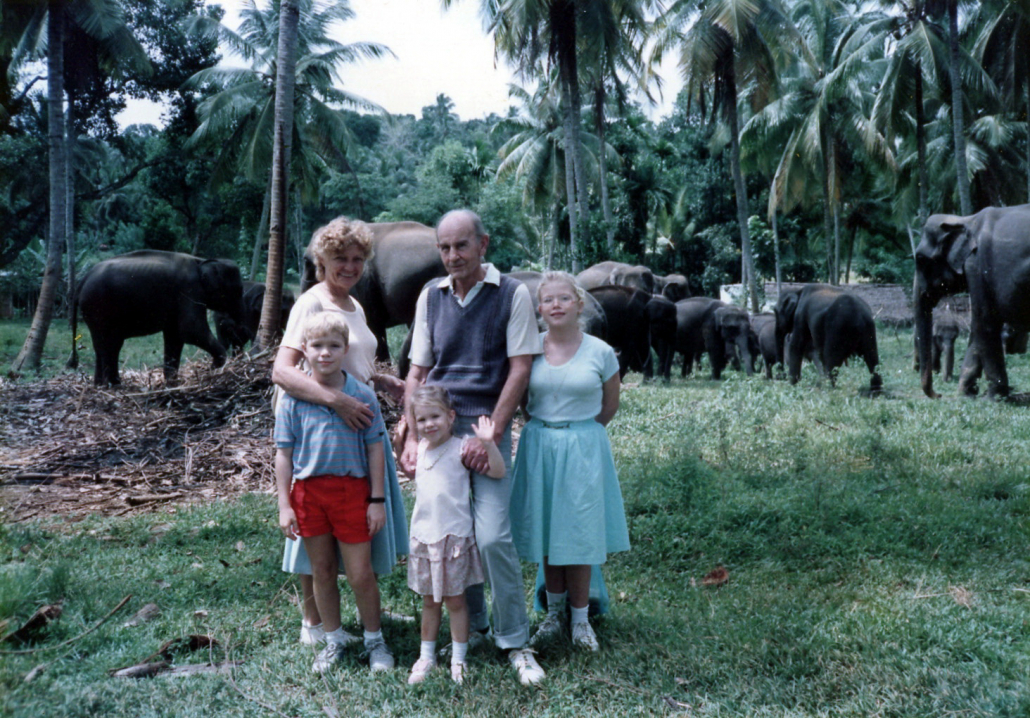

The life and relationship of Hanny and my father were a example that all his children and Californian grandchildren praised. All loved to be with him at their house. Sandy’s oldest child became like a step-daughter to them, even taking the “Reusche” name (her father was Robert Weich). Kim felt the responsibility to look after her siblings after the death of their mother, and she staked out the house of my father and Hanny as her exclusive domain. I’m sure that Sandy asked them to look after Kim, John and Daren before she died. My father and Hanny were in the middle of the events that suddenly identified her last-stage cancer, and lead to her death too soon thereafter.